The plastic waste crisis - Assessment & call for actions

The road to heaven is paved with fortunate mistakes. The road to hell is paved with good intentions.

In the early 2000s, Alex Atala, the world-renowned Brazilian jungle cook bought 62’000 acres of Amazonia land to implement “sustainable farming” and improve the lives of local communities. To gain the tribes’ sympathy, he sent along donations of packaged staples of all kinds to the villagers in dire need. When the time came, he visited his newly bought land only to be shocked by the sight: piles of plastic wraps and bottles thrown everywhere. Upset and disappointed, he called a meeting of the villagers to lecture them about littering and tidy community upkeep. He came to a startling realization: it was rather his fault. As he writes in his book “D.O.M.: Rediscovering Brazilian Ingredients”, the tribe chief argued: “For us, the packaging of a fruit is its skin, a fish's are its scales, an ox's is its hide, and these things can all be thrown on the ground. You should not have sent us these things wrapped in plastic.”

We owe a lot to plastic. Affordable, durable, non-toxic, moldable in all shapes and dimensions, it is the one product that disrupted all industries in the XXth century and continues to do so even today. Plastic preserved many commodities and countless forests (by replacing wood). It conserved earth’s metals (by replacing iron, copper, and aluminum in many uses), spared numerous lands (by replacing cotton farming through nylon fiber) and ultimately saved entire ecosystems. Hence, this paper is not intended as a trial to bash plastic and throw blame. It aims to explain that the plastic era has reached a “tipping point” where producers and consumers need to rethink their need for / use of it. Let us begin with a little history review.

A brief history overview

It is hard to find an objective timeline for the history of plastic. As far as the first synthethic plastic ever made, an American historian would credit the work of Hyatt in 1863 with celluloid, a replacement for ivory billiard balls made from elephant tusks. [1]

A British source would argue that Hyatt simply copied Parkes patents from a decade prior, even lost a court ruling on the matter. The plastic’s storyline is twisted by tragic events as well. As retaliation for world wars, German contributions (although arguably the most significant of the XIXth century) will be overlooked or completely ignored. Precisely, the discovery of Polyvinyl Chloride “PVC” (a lucky accident) by Baumann and that of Polyethylene (another lucky accident) by Pechmann in the late 1800. Unlike celluloid, both products remain largely in use today[2].

I ended up with more questions than facts, especially about the biased way we manoeuvre to document our history. Nonetheless, here is a non-exhaustive list of some important milestones:

Earliest documented use of plastics was some 4000 to 3500 years ago: naturally occurring plastics were used in nose plastic surgeries in the Old Kingdom of Egypt and latex was used by the Olmecs of Mexico in a soccer-like ball game.

VIIIth to XIVth Century AD: development and documentation of the science and methods behind polymers and plastics during the Islamic Golden Age through the work of Al-Kindi, Ibn-Hayyan and Al-Razi.

Mid XIXth and XXth century: birth of synthetic plastics (celluloids, PVC, Polyethylene). 1950: first use of a polyethylene bag – the birth of single-use plastic.

Undeniably, “single-use” bags brought about mass-adoption. The fifties marked a shift in the general perception around plastic. Once an innovative material (Rolls Royce marketed its 1916 cars by emphasizing the use of plastic in it), plastic conveys a gloomier message today: a cheap, polluting material. So, what exactly happened starting 1950?

[1] The hunger for billiard in Europe and North America –a fading form of entertainment today- nearly wiped out elephants long before the blame was thrown on Asian traditional medicine. Alarmed by the declining number of elephants, billiard manufacturer Brunswick-Balke-Collender offered up a $10,000 prize for the best ivory substitute for making billiard balls. Hyatt’s product, celluloid, never got the prize but was patented as a potential alternative – although instable and occasionally exploding.

[2] Polyethylene is the most commonly used plastic today. PVC is the third most commonly produced with around 40 million tons each year.

Explosive growth

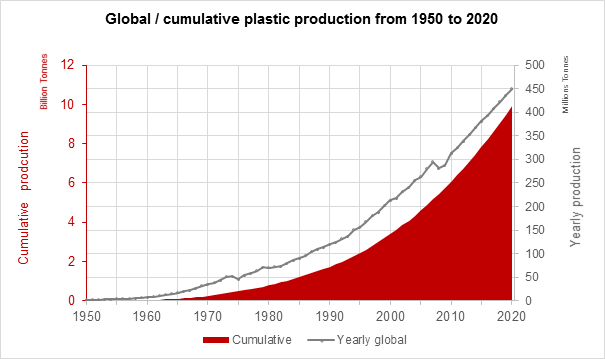

1950- 2015 data: Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., & Law, K. L. (2017). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science Advances, 3(7), e1700782

2015 – 2020 data: Mehdi Mezni, forecasted using linear regression

In 1950, the world plastic production barely reached 2 million tons per year.

By 2015, annual production had increased nearly 200-fold to 400 million tons. From 1950 to 2015, the cumulative plastic production worldwide reached 7.8 billion tons of plastic.

That translates to one ton of plastic for every person alive today. Nearly half of all the plastic ever manufactured has been made since 2000.

Clearly, production got off the rails. Plastics favored for their physical properties and economics flooded the markets. With no real plan to dispose of it, plastic trash started piling up quickly.

Plastic as an innovation

Food packaging is a good example of innovative plastic use. The affordable isolation and chemical stability of plastic over a large range of temperatures / humidities / and shelve time is essential to preventing food spoilage and contamination. From harvest all the way to end-consumer, plastic use is paramount for food safety and disease prevention.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) explains:

“Large losses from farm to plate are attributed to poor handling, distribution, storage, and purchase/ consumption behavior. Huge resources that could otherwise be spent on more productive activities go into producing and transporting goods that only go to waste. Losses at almost every stage of the food chain may be reduced by using appropriate packaging.”

Furthermore, this 2017 study by the University of Catania demonstrates that food waste has a greater environmental impact than plastic mishandling. In fact, a spoiled batch of food comes at an exorbitant cost. It means wasting all the resources invested in its production across its value chain: from agriculture to last mile store delivery (including water, fossil fuels for machinery and transportation, electricity involved in storage and packaging, and countless time down the drain).

Nevertheless, plastic is not always used skillfully.

The plastic packaging problem

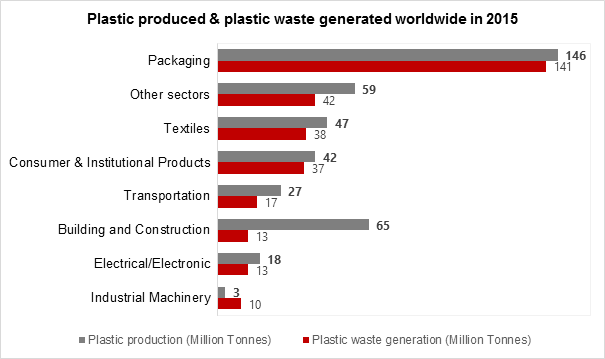

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., & Law, K. L. (2017) - Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science Advances.

N.B: Consumer and institutional products: includes kitchen goods, wastebaskets, storage bins, and similar items.

Packaging is the primary sectoral use of plastics globally, accounting for 42 percent (146 million tons) in 2016 and growing 5.6% a year.

Since packaging tends to have a much lower product lifetime than other products (such as construction or textiles), it is also dominant in terms of annual waste generation. It is responsible for almost half the global plastic waste.

For instance, in 2011, a million plastic bags were used per minute worldwide. Other sectors use plastic too like construction, kitchen goods, transportation and electrical / electronic products. However, that is a rather sustainable choice. “Construction plastic” as well as plastic in vehicles and planes remains in use for years, even decades, saving earth’s animals, forests, metals and limited resources.

Furthermore, recycling plastic coming from these industries is easier to implement and track. Hence, to tackle the real problem, plastic packaging (or over-packaging to be accurate) needs a thorough re-evaluation.

The average life span of a plastic bag is 12 minutes and needs a century to decompose. Only 5% of all plastic packaging is recycled worldwide. Recycling is not a long-term solution to the problem.

In Europe, 30% of plastic packaging is recycled twice at most before finding its way to a managed landfill.

The remaining is either incinerated or mismanaged and shipped/smuggled (mostly to west Africa since the 2018 Chinese ban on waste imports) as reusable material or humanitarian relief before ending in dumps like Agbogbloshie near Accra, Ghana or Dandora, near Nairobi, Kenya. Agbogbloshie landfill, near Accra, Ghana – Romano Maniglia

Addressing the over-packaging crisis

The complexity of plastic crisis translates the need for full measures to be implemented. Acknowledging the problem (the biggest being over-packaging / unnecessary plastic packaging) from all stakeholders is mandatory to begin with.

Then, it is paramount to reduce the demand for plastic in packaging. Finally, breakthrough alternatives with similar properties and great economics will seal the fate of unnecessary plastic use.

We suggest the following solutions to be implemented, advocated for, enforced and encouraged (sorted by urgency):

- Worldwide ban of plastic trash export with the highest scrutiny (Interpol involvement): trash export merely displaces the problem and makes it harder to contain.

- Use of paperboard packaging where possible.

- Improvement of current packaging design to minimize the use of plastic.

- Inter-continental collaboration to enhance plastic recycling efficiency through standardization of procedures.

- Creating incentives for greener products and to encourage public to recycle (examples: Hong Kong’s Green Coin program, Sainsbury’s reverse vending machine)

- Use of biomaterials that rapidly decompose into natural components.

From a judiciary standpoint, a global effort to ban needless plastic packaging should be mandated. Plastic usage in packaging remains largely deregulated.

A “plastic credit” (similar to the “carbon credit” system; not a pass-through tax that end up in the end-consumer’s hand) may allow market mechanisms to drive industrial and commercial processes in the direction of less plastic intensive usage.

Unnecessary plastic applications that should be banned typically include:

- Last-mile plastic shopping bags.

- Individual plastic wrapping of any items that are not perishable or already inside a hermetically sealed package.

- Plastic clamshells for electronic supplies.

- Unnecessary plastic uses or uses wherever paper / carton options exist (6-pack rings, coffee cup lids, straws, pizza savers, single-use “party” appliances like cups and plates).

A final word

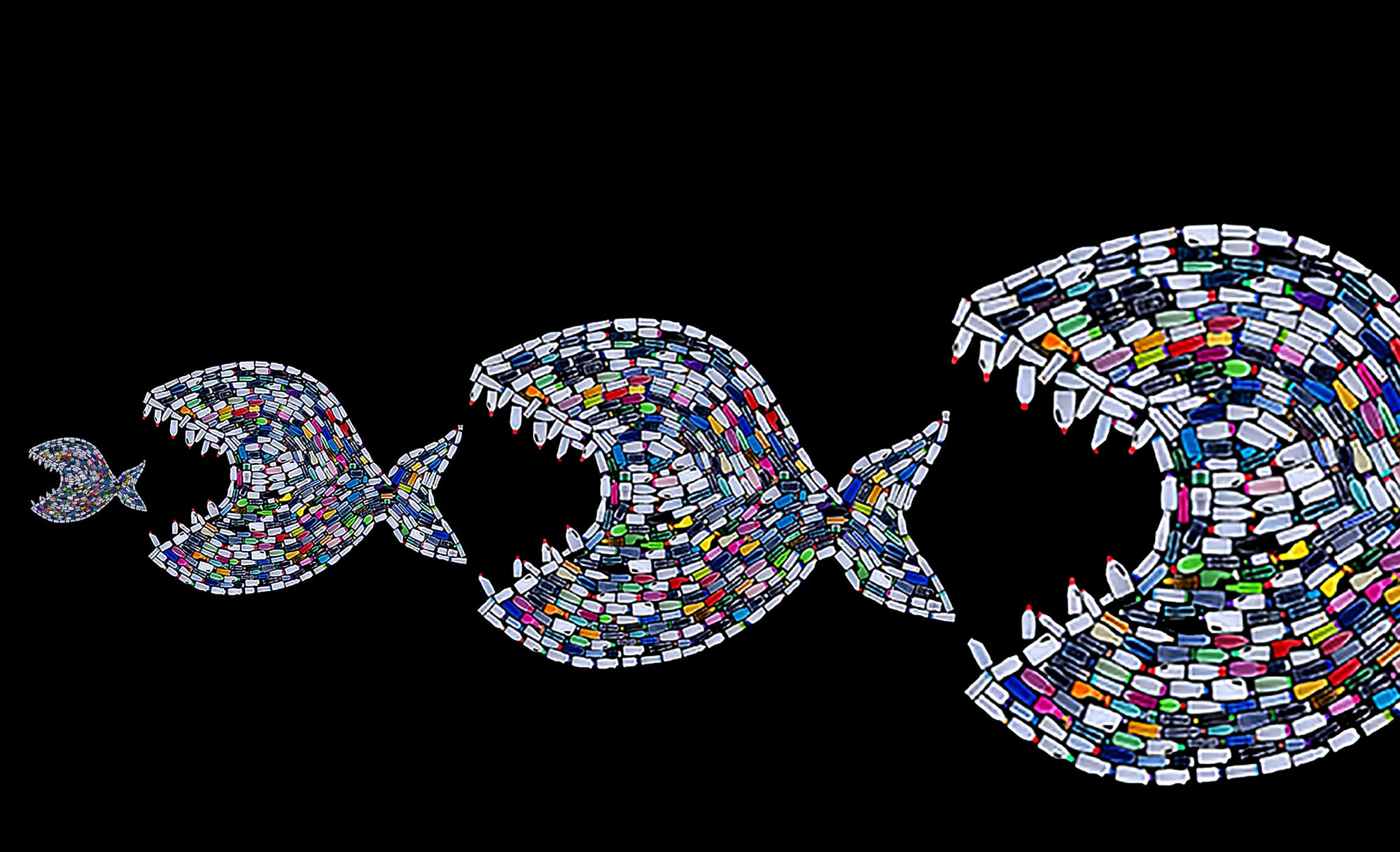

Plastic has a fascinating story to tell. One that marinated in fortunate accidents and matured in wars. Through thick and thin, plastic prevailed and planted its roots in human history like a proud sphynx. Given its economics, versatility and stability, plastic overwhelmed the human-ruled planet. It sure saved its forests and preserved its metals but started to clog its oceans.

Largely due to deregulation, plastic trash’s mishandling and misuse has prompted an environmental crisis that shook our biosphere to the core. Data suggests that plastic packaging is the root-cause behind the crisis.

We stand at a crossroad where our negligence cannot be tolerated anymore. Actions to curb the demand for new plastic in packaging need immediate implementation.

Furthermore, cutting-edge technology and better product design shall be given more funds and focus rather than recycling slogans to win over undecided voters. For politicizing such a crisis only makes it worse.

Keywords: Plastic, packaging, sustainability, recycling

Mehdi MEZNI - 2021